Algerian-Jewish refugee in France: ‘We were seen more as Arabs’

Despite a mostly happy childhood, Madeleine Sabbagh experienced some antisemitism from her French settler classmates in Algeria. She explains to the Jewish medium Tenoua the circumstances of her arrival for France – a shock on many levels.

What was the situation like for your Jewish family in Algeria? Did you experience anti-Semitism?

I grew up in a modest Jewish family. We weren’t religious, but traditions were important, especially the holidays of Passover and the Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur. Since the age of 5, I’ve always fasted; it’s a reminder of our ancestors. Life wasn’t easy on a daily basis; we weren’t rolling in money. My father was a tailor; he sometimes traded fabrics for boiled eggs so we could have something to eat. My brother didn’t have schoolbooks like his classmates… we couldn’t even afford those kinds of things.

I remember some girls saying to me, “You’re pretty for a Jew. Are you really Jewish?” I heard that two or three times. I was about ten years old. At the time, there was a sort of separation between Jews and Catholics, whom were called settlers. We didn’t really socialize, except at school, but it didn’t go much further than that. We were almost closer to the Arabs. We had more similar ways of life, even though our cultures were different. I remember a friend at the Mostaganem high school calling another girl a “dirty Jew.” The principal didn’t react; that was how it was at the time. The feeling of being Jewish in a world that rejected us was even harder to live with than poverty.

How was your departure for France organized?

I left around May 1962. There was one boat a day, so everything was done in a hurry. On July 5th, Independence Day, there was a terrible massacre in Oran, 80 kilometers from Mostaganem. That day, while a crowd from the Muslim suburbs was celebrating independence in the European neighborhoods of the city center, everything went downhill.

A large number of French people were lynched, captured, mutilated, massacred. Some were beaten to death, others thrown into the lake. We weren’t expecting it at all; it was supposed to be a day of celebration. A real massacre. Many people we knew died that day. The Arabs entered homes and killed people in their homes. This caused a wave of panic among the French people of Oran. Many fled in a hurry afterwards. We still don’t know exactly how many died. But for us, the pieds-noirs, that day remained a shock, a trauma.

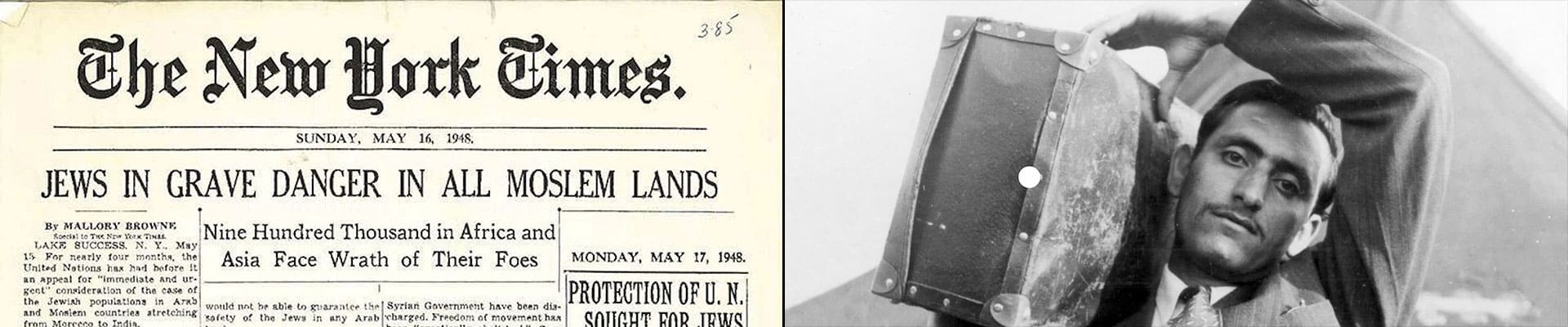

Fortunately, I had already returned to France to take my baccalaureate. I made several stops before arriving in Paris, staying with those who were willing to welcome me. I stayed with aunts and cousins, all over the place, with my belongings. My parents arrived six months later. They tried to save what they could, but it was complicated, and we were all affected by the deteriorating situation in Algeria.

How did you experience it at the age of 19?

Leaving also meant leaving those you loved. My grandmother died just before I left, and my grandfather was left alone. When I went to see him, I knew it was the last time. He was in the courtyard calling my name; we both knew it was over. It was heartbreaking to leave, to leave my family, to no longer be able to visit my grandparents’ graves. It’s a void, a pain that you carry for a long time. My grandfather died shortly after I left. That’s how it was; you couldn’t take everything with you; you left everything behind, including your roots.

How were you received in France? What life change did it represent for you?

We were very badly received n France, where there was still an anti-Semitic climate. There was neither sympathy nor indulgence. We were seen more as Arabs than as French here. We were eligible for assistance for repatriates, but we had to queue for hours. With that money, I was able to buy a coat and fur-lined gloves, because I had nothing to wear, especially not warm clothes. It was very cold in Paris, it was raining, it was grey. We got a violent shock on all levels.

Leave a Reply