Mizrahi Jews in Israel have largely caught up with Ashkenazim

The term ‘Mizrahi’ to designate Jews from Arab countries is a misleading one, argues demographer Sergio della Pergola in JIMENA’s Distinctions magazine. Better to talk of Jewish communities from Christendom and the Muslim world. Gaps in Israel between these two groups have narrowed significantly over time, he writes, but should disappear in another generation.

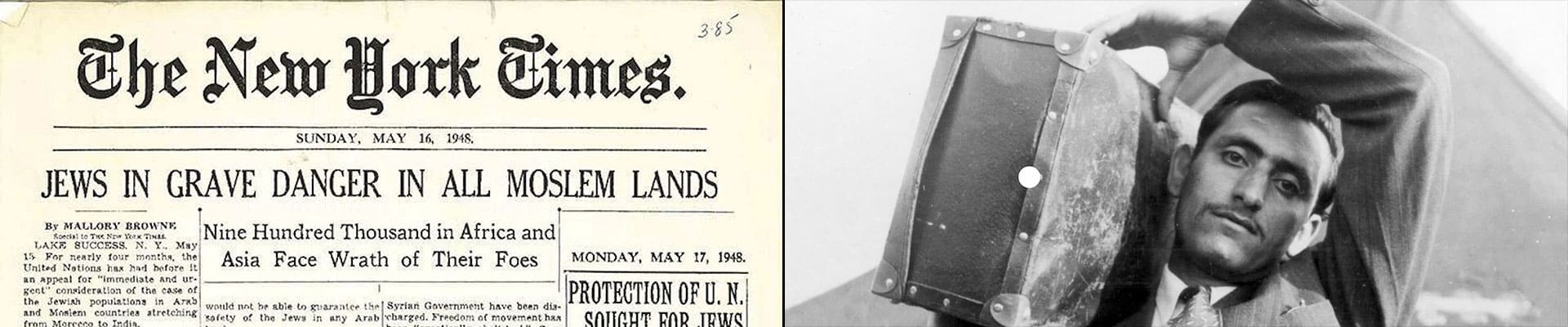

In the late 1940s, 1950s and early 1960s in particular, significant educational and occupational differences emerged among the Jewish migrants who chose to go to Israel versus those who ended up in Western Countries, such as France. Israel absorbed fewer highly educated migrants with professional or managerial backgrounds, and instead drew in more semi-skilled and unskilled workers in blue-collar industries, the service sector and agriculture. Israel also attracted higher percentages of children and elders than did Western countries, resulting in much heavier dependency rates.

The more problematic fact was that socioeconomic differences between Eastern European and Mizrahi Jews who migrated to Israel were much smaller than the differences between migrants from Asia and Africa who split between Israel and the West. Therefore, the widening socioeconomic differences that emerged between Jews from different continental origins during the subsequent integration in Israel were the result of factors operating in Israel, not abroad.

Clearly, the Jewish migrants to the State of Israel, no matter their regions of origin, had lower occupational skills and socio-economic status than the Jews already established there — not to mention lower seniority in the country, both as individuals and as immigrant communities. Therefore, the absorption of the new immigrants was tougher in Israel than in the Western countries, where those gaps were less pronounced.

A notable process of downward mobility was shared among the new immigrants. The starting points for immigrants originating from Asia or Africa actually were somewhat lower compared to those who arrived from Europe or America, and as a result, it should be acknowledged that the price the Asian and African immigrants paid in the first years for their adaptation in Israel was much heavier. They suffered a much more significant initial loss of social status than European and American immigrants, as they were less able to keep the socioeconomic positions they held abroad before migration and had to relocate at lower levels of the social ladder. Therefore, during the first absorption period in the State of Israel, the gaps that already existed abroad between the various groups of origin much deepened to the disadvantage of those from Asia and Africa. With this, sediments of bitterness were created in Israel, which would not be forgotten in the following decades.

What followed — gradually but consistently — was significant upward mobility, eventually reducing the achievement differences in educational levels, occupational stratification and income of the various origin groups, along with the already noted demographic convergence. Starting with the late 1960s, an intense process of upward occupational promotion emerged in Israel, with a parallel social rise of the two main origin groups. The percentage of those with academic and technical skills steadily increased among all origin groups. The percentage of laborers and agricultural workers decreased steadily and reached similarly low percentages among all origin groups, also reflecting some substitution at the lower social levels by Palestinians and later by foreign workers.

To fully emphasize the social significance of such occupational catch-up, one must compare the data for those born abroad and those born in Israel of the same origin. The occupational/social-class gaps narrowed much, especially as measured by the ratio between the two origin groups at the top level of the ladder, but gaps did not disappear in the second generation. To demonstrate: In 2021, the rate of persons employed in jobs requiring at least partial academic studies was 36% among those born in Asia or Africa versus 58% among those born in Europe or America, a gap of 22%. Among the second generation (those born in Israel whose father was born in Asia or Africa), the same percentages were 57%, compared to 71% for those born in Israel whose father was born in Europe or America — a gap of 14%. The gap was not only narrower, but at a far better occupational profile. The crossover point when the majority of immigrants and their children shifted from lower to higher status jobs occurred in the 1980s among immigrants of Europe or America origin, and around 2010 among those of Asia or Africa origin. More time — at least one more generation — still is needed for social class equalization to be completely attained, along with further blurring of origin boundaries through continuing intermarriages.

Another analytic angle is offered by examining the role and composition of the elites in Israeli society. Jews from Asia or Africa were able to achieve a visible presence — although not yet always the exact proportionality — in all avenues of the leading strata in Israel, with only two remarkable exceptions: As of 2023, no representative of the origin group yet had been prime minister or president of the Supreme Court. All other possible targets of a fair representation were achieved, including the presidency of the state, the top economic elites, the military, academia, in the Knesset, in the local authorities, in the trade unions, in the popular performing arts, and among outstanding athletes.

Leave a Reply