The Moroccans building Israel’s dust city

As you drive down the main drag into the city you’ll see a name atop a few of the new apartment towers—AVISROR—and then on buildings all over town, so I decided to start my investigation by understanding what that meant. AVISROR seemed like it could be some kind of conglomerate: Israelis in construction, maybe some blurry Putin money or a multinational connecting the Negev with Hungary and the Punjab. It turned out to be the name of a local Beersheba patriot, formerly a peddler of dates and arak from the hinterland outside Agadir, Morocco.

The Zionist heroes that Ben-Gurion thought would make the Negev bloom were probably suntanned kibbutz socialists and not Moshe Avisror, who appears in one picture with a white suit, matching fedora, prayer shawl, and sunglasses. Moshe and his sons aren’t kibbutznik socialists. Neither are they American-style developers with business-school degrees. Their walls feature paintings of North African rabbis, like the cloaked miracle worker Baba Sali. These are the people who built Beersheba, and who are now knocking parts of it down to build it higher.

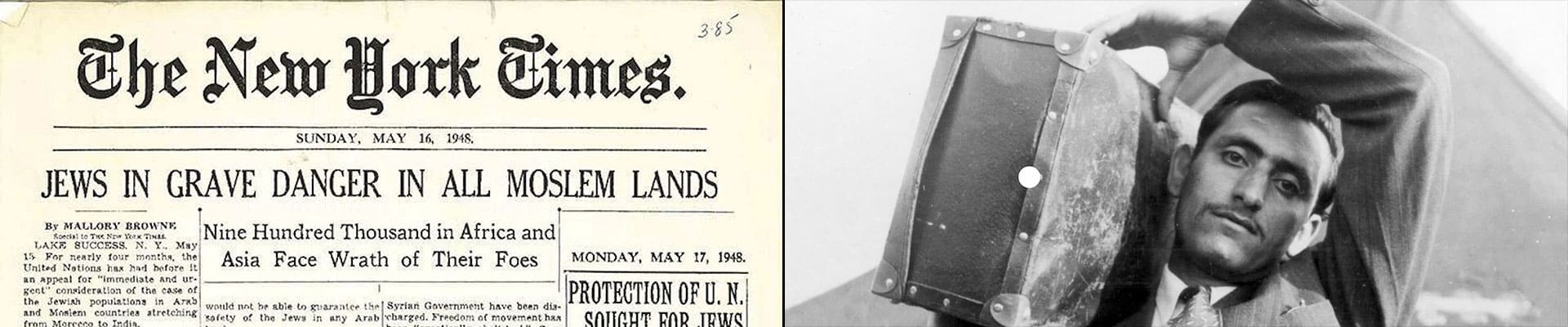

Moshe Avisror was a young father in January 1963, when he and his wife, Esther, (whom he married when he was 13 and she 12) took their four kids and left Morocco, sneaking past government spies and police, trying not to attract attention on the bus to Casablanca before sitting amid cargo crates on a transport ship to Marseilles. At the French transit camp Avisror’s kids saw snow for the first time. They didn’t have much time to enjoy it, though, before they sailed to Haifa, then drove overland at night into the desert to a place called Yeruham, which turned out, when the sun rose, to be a dusty cluster of tents. Zion!

Moshe spoke only Moroccan Arabic and had no formal education, just Torah and years of living by his wits in the marketplaces around Agadir. It was enough. He got a job hauling cement blocks, then building a kindergarten and then a few rooms at a school. Then he built a whole school.

In 1973 Moshe bought land for a home down the road in Beersheba, which the government had started calling the “capital of the Negev.” The name was aspirational. The city was a backwater of apartment blocks thrown up quickly to house immigrants, grouped in neighborhoods that weren’t even known by names, just letters of the alphabet. The old part of town, where the Arabs had fled the Jews in 1948 and were replaced by Jews who’d fled other Arabs, was a slum.

In the early days, Avisror’s construction workers were Moroccans, including Moshe’s own sons. One of them is Eli Avisror, the current CEO, a gravelly character in jeans and a white polo shirt; another is Jacky, Eli’s deputy, a more fashionable type in tortoiseshell glasses whom I bumped into at the Roasters in one of the Avisror condo developments. (The paterfamilias himself is ailing, and unavailable for interviews.) After a while, the Jews didn’t want to be workers anymore. They wanted to be managers, and now, Eli growled, “Everyone thinks they’re a developer.” These days, the company’s working hands belong mostly to men who come from China or from Palestinian towns in the West Bank.

The turning point for the family business, and for the city, Eli told me, came in the early 1990s with the great wave of immigration from the former Soviet Union. This human movement that accompanied the collapse of the Soviet empire was perhaps the biggest stroke of luck in Israel’s history, proof that God gives this country what it needs (though not necessarily what it wants). This time, His gift came in the form of a million Jewish atheists.

The Russians needed homes and Beersheba needed people. Today a quarter of the people who live here were born in the Soviet Union. In a closely related piece of trivia, Beersheba has more chess masters per capita than anywhere else in Israel.

By 1997 the Avisrors had raised a building that was seven stories tall, towering over most of downtown—Avisror House, with the company offices on the top floor. Seven stories now seems quaint in light of the company’s new cluster of 30-story towers, the city’s tallest.

Real estate prices in central Israel are so hot that they’ll probably go up 5% before I finish writing this sentence, but here they’re flat. The most recent numbers from the Central Bureau of Statistics, from 2019, show more people leaving the city than coming, a net loss of 1,114—while Netanya, which is the same size and at roughly the same midpoint in Israel’s socioeconomic rankings, but closer to Tel Aviv, gained 2,298 new residents. New housing units are going up in Beersheba anyway, more every year—910 in 2017, more than double that the following year, and inching upward since then—rising next to the new malls and next to the city’s great hope, the hi-tech park.

The collapse of the Soviet empire was the biggest stroke of luck in Israel’s history, proof that God gives this country what it needs (though not necessarily what it wants). This time, His gift came in the form of a million Jewish atheists.

The success of the hi-tech park could propel the city closer to what it wants to be. The army is supposed to transfer its main technology units here from bases around Tel Aviv, but the move has been delayed because the kind of Israeli who serves in tech units in Tel Aviv isn’t the kind who wants to live in Beersheba.

Then there’s the university. Ben-Gurion University of the Negev is a world-class institution with, by all accounts, the best student life in Israel. The social buzz on campus, the hangouts under the rosewood trees on Ringelblum Street, the first-rate veggie Indian restaurant—you’re unlikely to meet anyone who studied here and didn’t love it, or to meet anyone who studied here and stayed. The jobs just aren’t here. Beersheba produces more engineers than any other Israeli city, but the economy that needs them is around Tel Aviv, which over the past 20 years also happens to have become—to Israel’s fortune, and the misfortune of every other city in the country—one of the coolest places in the world. How can other cities compete? So the students come to Beersheba and have a great time, they study and snooze on the grass and fall in love on the campus, which was built by some incomprehensible logic as a concrete castle fortified against the native peasantry. The students don’t mix much with the locals, and once they get those degrees they’re gone.

Real Beershebans are used to people leaving. It stings, but you don’t live here if you don’t have thick skin. The city’s secret weapon is its fierce local patriotism, a force not entirely intelligible to an outsider, but which is one of the most compelling aspects of the place. Eli Avisror is a wealthy guy, he owns apartments in Tel Aviv, but wouldn’t dream of living anywhere but Beersheba. His four kids and 10 grandkids all live here. Why? Southerners are warm, he said. The city is like a family, and whether you’re celebrating or mourning, no one’s door is ever closed.

Leave a Reply