Lucette Lagnado: when Jews fled Arab lands

The acclaimed Egyptian-born author Lucette Lagnado has chronicled her own refugee parents‘ stories in her books. Witnessing the UN conference on Jewish refugees last month, when Israeli officials ‘turned the tables’ on Palestinians, she now describes in the Wall St Journal the trauma of other Jewish refugees from Arab countries, whose cause is moving to prominence in the Middle East debate. Only the expression ‘Arab Jews’ grates (with thanks: Dan, Niran, Desi, Lily):

Mrs. Abadie, now 88, remembers watching attackers burn prayer books,

prayer shawls and other holy objects from the synagogue across the

street. She heard the screams of neighbors as their homes were invaded.

“We thought we were going to be killed,” she says. The family fled to

nearby Lebanon. Mrs. Abadie left behind all she had: clothes, furniture,

photographs and even a small bottle of French perfume that she still

misses, Soir de Paris—Evening in Paris.

The Abadie family’s story is moving

from the recesses of history to a newly prominent place in the debate

over the future of the Middle East. Arab leaders have insisted for

decades that Palestinian refugees who fled their homes following

Israel’s creation should be allowed to return to their former homes.

Now Israeli officials are turning the

tables, saying the hardships faced by several hundred thousand exiled

Arab Jews, many forced from their homes, deserve as much attention as

the plight of displaced Palestinians. “We are 64 years late,” says Danny

Ayalon, Israel’s deputy foreign minister.

“The refugee problem does not

lie only on one side.” Mr. Ayalon, whose father is an Algerian Jew, led

a U.N. conference last month sponsored by Israel and dubbed “Justice

for Jews From Arab Countries.”

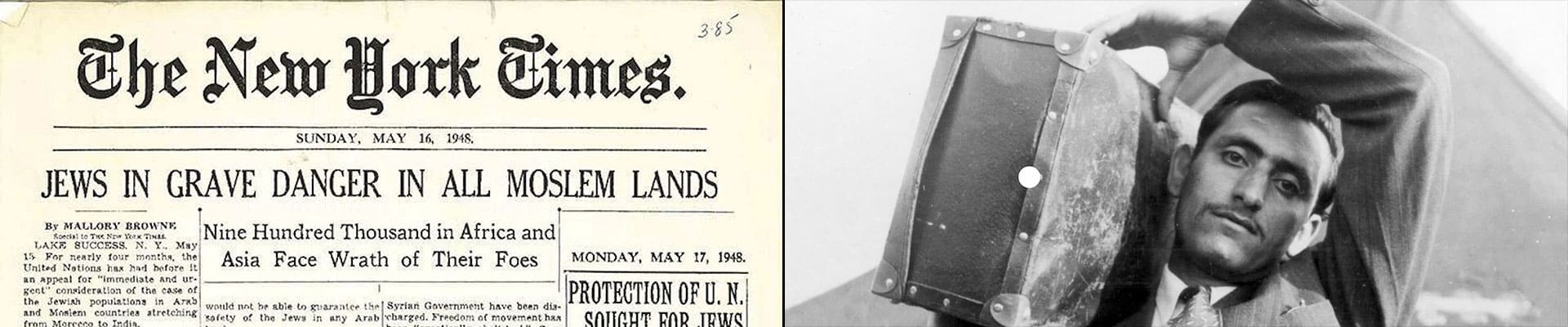

Before the establishment of Israel in

1948, an estimated 850,000 Jews lived in the Arab world. In countries

across the Middle East, there were flourishing Jewish communities with

their own synagogues, schools and communal institutions.

Life changed dramatically by 1948 as Arab governments declared war on

the newly created Jewish state—and on the Jews within their own

borders. At the U.N., an Egyptian delegate warned that the plan to

partition Palestine into two states, one for Jews and one for

Palestinians, “might endanger a million Jews living in the Muslim

countries.”

Wedding of Mamus and Dora Rumani in Benghazi, Libya, circa 1955.

Jews began

fleeing—to Israel, of course, but also to France, England, Canada,

Brazil, Australia, New Zealand and the U.S. Yemen was home to more than

55,000 Jews; in Aden, scores were killed in a vicious pogrom in 1947. An

airlift dubbed “Operation Magic Carpet” relocated most Yemenite Jews to

Israel. In Libya, once home to 38,000 Jews, the community was subjected

to many brutal attacks over the years. In June 1967, there were

anti-Jewish rampages; two Jewish families were murdered—one family

clubbed to death—and schools and synagogues were destroyed, says

Vivienne Roumani, director of the documentary “The Last Jews of Libya.”

“We were there for centuries, but there is no trace of Jewish life,” she

says.

Among the Jews forced out of their homes was my own Egyptian-Jewish

family, departing on a rickety boat in the spring of 1963. Egypt had

once been home to 80,000 Jews. My parents, both Cairenes whose stories I

chronicled in two memoirs, were especially pained at leaving a country

they loved, without being allowed to take money or assets.

Within 25 years, the Arab world lost nearly all its Jewish

population. Some faced expulsion, while others suffered such economic

and social hardships they had no choice but to go. Others left

voluntarily because they longed to settle in Israel. Only about 4,300

Jews remain there today, mostly in Morocco and Tunisia, according to

Justice for Jews From Arab Countries, a New York-based coalition of

groups that also participated in the U.N. conference.

Many of the Palestinians who fled Israel wound up stranded in refugee

camps. Multiple U.N. agencies were created to help them, and billions

of dollars in aid flowed their way. The Arab Jews, by contrast, were

quietly absorbed by their new homes. “The Arab Jews became phantoms”

whose stories were “edited out” of Arab consciousness, says Fouad Ajami,

a scholar of the Middle East at Stanford’s Hoover Institution. “We are

talking about the claims of the Palestinians,” he says. “Fine, but there

were 800,000 Arab Jews, and they have a story to tell.”

Palestinians bristle at the effort to

equate the displacement of Arab Jews with their own grievances. Hanan

Ashrawi, a member of the Palestine Liberation Organization’s Executive

Committee, says Mr. Ayalon “opened up a can of worms for political

purposes” with the U.N. conference. She says that Israeli officials are

trying to use a “forced and false analogy…to negate or question

Palestinian refugee rights.” The Palestinians, she says, “have nothing

to do with the plight of the Jews or other minorities who left the Arab

world.” Still, Dr. Ashrawi recently proposed that Arab Jews should also

have a “right of return” to the countries they left.

At the U.N. conference, Mr. Ayalon

called Dr. Ashrawi’s suggestion to have Jews return to Arab countries

“totally ridiculous.” Mr. Ayalon and the Israeli government are pushing

ahead with efforts to raise the profile of Arab Jews. Israel has pledged

to establish a national day in honor of Arab Jews and build a museum

about their lost cultures. Mr. Ayalon has decided to make the

Arab-Jewish refugees part of any negotiations, which has never been the

case before. Looking ahead to a settlement, he would like to see both

Palestinian and Jewish refugees compensated by an international fund.

Meanwhile, the Israeli ambassador to the U.N., Ron Prosor, has called on

the U.N. to research the refugees’ history.

Mrs. Abadie attended the conference

with her son Elie, now a physician and rabbi who leads Congregation

Edmond J. Safra, a Manhattan synagogue attended by Lebanese and Syrian

Jews. Until 1947, Syria had an estimated 30,000 Jews living in Aleppo

and Damascus. But like Mrs. Abadie, many departed in the wake of the

violence that left 75 dead and synagogues in ruin.

The Abadies were refugees twice. After

leaving Aleppo, the family ended up in Beirut, Lebanon. For a time, life

was good in the cosmopolitan city. But by 1970, the climate had turned

hostile. Armed militants appeared in the streets. Rabbis, including

Elie’s father, Abraham, had their pictures posted in the city’s mosques,

identifying them as “Zionist-Jewish leaders,” an act the family took as

a death threat. The Abadies decided once again it was time to move.

Some Jewish refugees, like Sir Ronald Cohen, find hope in the new

initiatives to call attention to Arab Jews. Mr. Cohen, a London-based

businessman, was a student at a French Catholic school in Cairo in 1956,

friendly with his Muslim and Christian classmates. His father owned an

import-export firm that specialized in appliances, and “Ronnie,” then

11, loved to visit him and play with the radios.

Then in October 1956, Israel, France

and England waged war against Egypt over the Suez Canal. Mr. Cohen’s

parents pulled him out of school after another Jewish boy was injured.

His mother, a British citizen, was placed under house arrest. His

father’s business was “sequestered”—effectively taken from him—and he

wasn’t welcome at his own office. In May 1957, the family left on a

plane bound for Europe. Mr. Cohen still remembers his father crying on

the plane. “There is nothing left here,” he recalls his mother saying.

“It is all over.”

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Jews

continued to pour out of the Muslim countries. When Desiré Sakkal and

his family left Egypt as stateless refugees in 1962, he says, “there

were very few Jews left.” Stranded in Paris in a hotel, Mr. Sakkal’s

little brother was diagnosed with cancer, and he still remembers how his

parents went to the hospital every day. The brother died a year later

in New York, at the age of 10. Mr. Sakkal went on to found the

Historical Society of Jews from Egypt, which seeks to recall the life

left behind.

The Six-Day War of June 1967 brought

some of the most violent anti-Jewish eruptions. As Arab countries faced

defeat by Israel, they turned their rage on their own Jewish

residents—what remained of them. In Egypt, Jewish men over 18 were

rounded up and sent to prison. Some were kept for a few days. Others,

like Philadelphia Rabbi Albert Gabbai, a Cairo native, remained

imprisoned for three years. Rabbi Gabbai was only 18 when he was thrown

in jail, along with three older brothers. He still remembers the cries

of his fellow prisoners—Muslim Brotherhood members who were being

tortured—echoing through the jail. He and his brothers feared that they

were going to be killed. After three years of “despair,” he says, they

were driven to the airport and escorted to an Air France

flight.

Mr. Cohen, who left Egypt in

1957, grew up to become a pioneer in European venture capital and

private equity. In recent years, he has worked to develop the

Palestinian private sector. He believes that the focus on Jewish-Arab

refugees could spur the Arabs and Israelis toward peace. “There are

refugees on both sides, so that evens the scales, and I think that it

will be helpful to the process,” he says. “It shows that both sides

suffered the same fate.”

2 Comments

Speaking of denial of suffering, the Italian writer Cesare Paese wrote that:

L'offesa piu atroce che si puo fare a un uomo e' negargli che soffra

The most atrocious thing that you can do to a man is to deny that he is suffering.

So the PLO/PA, Ashrawi, HaArets and the rest of the gang are committing the most atrocious offense, according to Pavese.

For Hanan Ashrawi to describe the raising case for Jewish refugees as the opening of a can of worms is a very curious analogy indeed.

http://www.answers.com/topic/can-of-worms

Is she afraid that the case for Palestinian refugees will cease to be viewed as a black-and-white issue with all right on the Arab side and all wrong on the pro-Zionist side?

(We know the answer.)